According to the Samaritans, 4,912 people died by suicide in the UK in 2020, and men aged 45-49 have the highest suicide rate. These are heartbreaking statistics, and we can barely imagine the pain families who experience such loss go through.

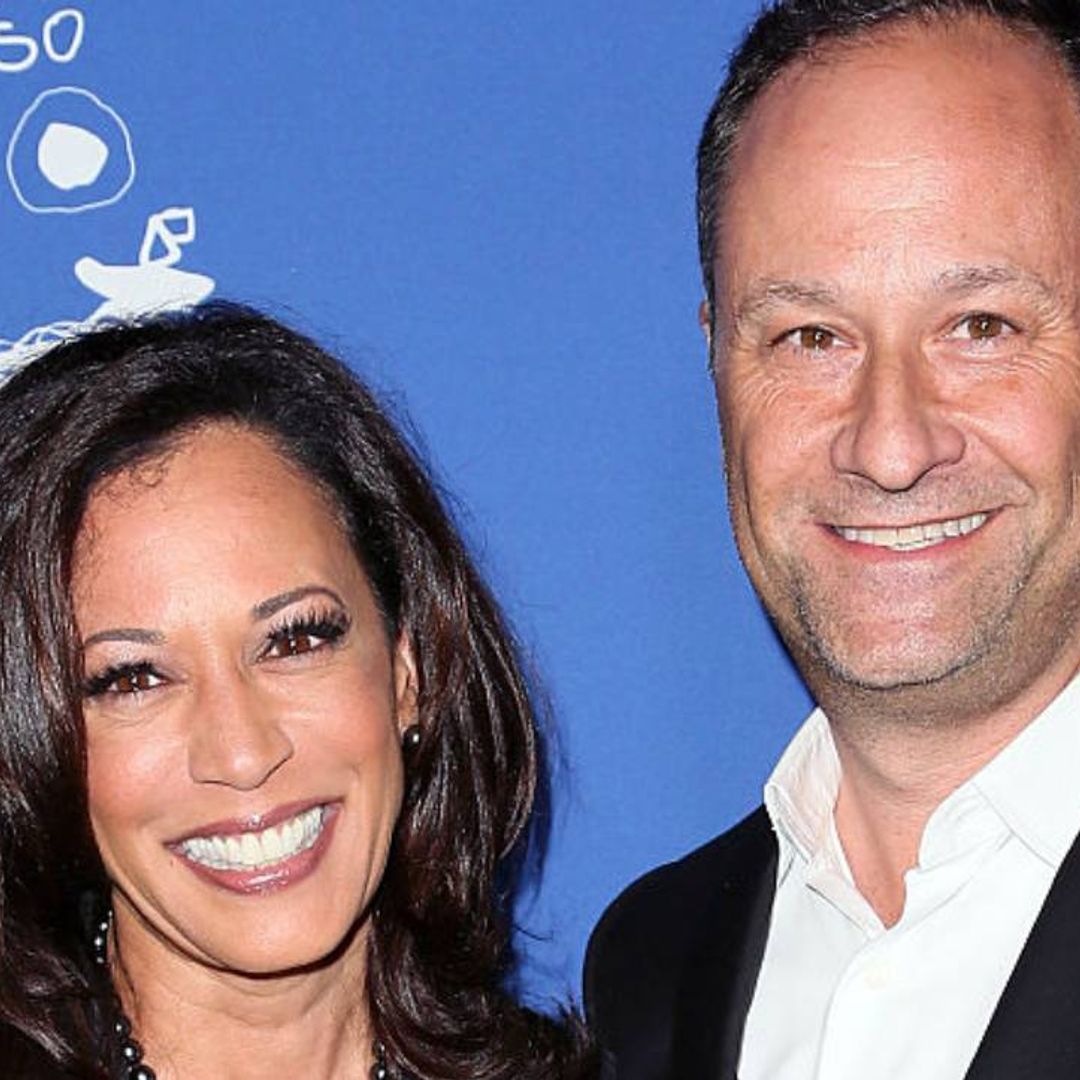

Mum-of-two Mia Scally, 34, a Lecturer in Forensic Psychology/Criminology at Middlesex University, lost her husband Damon to suicide in 2014.

READ: 5 ways to support your family's mental health during the pandemic

Mia, Damon and their two children Robin and Jasper

Damon, then 28, was a successful brand manager with the betting company Ladbrokes. The couple were together for ten years after meeting at college in Lincoln, happily married for seven years and in 2009 bought a home together in Chesham, Buckinghamshire. They had two children, son Jasper, then aged three, and Robin, then six.

The shock of Damon's death was monumental. Along with dealing with her own grief, Mia had to explain what had happened to her children and comfort them as they grieved.

As the family tried to process their devastating loss, Mia searched for a book for Jasper and Robin about helping children affected by suicide, but there was little available. It was then that the trio decided to write their own book to support other children going through the same circumstances.

Below is the inspirational story of the Scally family, who together have produced Everything Changed, an illustrated children’s e-book and paperback in the words of Robin, now 13, and Jasper, 10. The book details how they felt after their dad’s death and how gradually they began to move forward with their lives.

In the book, the children say: "It will never be ok, and I will always miss my Dad. Especially when awesome or really sad things happen. But we are getting through it day by day together. Each day feels a bit different. Some days I still feel sad but other days I smile lots. Our daddy is always with us in our hearts and in our memories."

Proceeds from the book (self-published through Kindle Direct Publishing) will go Child Bereavement UK, the charity that supported the family with their grief.

Here, Mia Scally tells her story to HELLO!...

Damon's death

On the day that Damon went missing and I got the phone call to say, 'Do you know where he is?' I never thought that [suicide] would have been what happened.

At first, I was just sobbing. Robin and Jasper knew something was going on and I sat them down and I said, 'Look daddy's not going to be coming home'.

The first thing I said was, 'There was an accident'. Then I kind of stopped and I thought, why am I telling them this? This isn't about them or me, this is about what I think I'm supposed to say. Then I said, 'Actually it wasn't an accident, daddy wasn't thinking clearly and he decided that he didn't want to be alive anymore, and he was very unwell and he made the decision to die.'

It's a lot for them to take on. Firstly, they are taking on that it was a choice and a decision. Actually, I think they processed that part much later.

At the time, regardless of how it happened, all they're hearing is, 'Daddy's not coming back'. He's not here and he's not going to be here later. They don't even understand what that means, not really. I think children think everything is so temporary and they think someone's going to fix the problem, and it's not one that can be fixed.

I lost about 10 kilos over the space of about two weeks. It was very clear that I wasn't ok. If you're pretending to children that that's normal, you're just teaching them to hide their emotions. They need to understand that it is something that's really upsetting. I'm a human being – I am going to be sad sometimes – but for some reason as parents, we feel that we shouldn't put that on the children.

And that's right. I would never put it on my children. I don't sit there and go 'make it better', but if I am upset, how else are your children going to learn that there's someone upset in the street, you go over and ask if they are ok?

I think the household has to reflect the reality of the situation. Their world has just come tumbling down and if they walked into a house that was like Disneyland, I just can't even imagine.

READ: 15 celebrities who have bravely opened up about mental health

The family at their children's christening

Mia's grief

I took three months off work when it happened and I would sit in my car outside of the school after I dropped the children off. I'd cry and then I'd drive to the burial ground and I'd park there and stay there all day until I had to go back to school and pick them up. I would just sit there and think and think and think and process.

For my husband, there was no choice. There was only one solution to how he was feeling. To me, it's irrelevant whether he fell or whether he jumped – in the grand scheme of things, I'm still left picking up the pieces. I wonder what could I have done? Where did I go wrong? Could things have been different? Who knows?

What's bizarre is I would have said Damon was someone who was open with his feelings at the time. I would have said if he had a problem he would have come and talked to me about it. But actually, I don't think that's the case.

I think men have this skill – at least my husband did – whereby they can give you enough so they feel they are sharing with you, and actually life is so busy that you don't realise that they're not actually sharing with you. Not really. Not in terms of the impact of emotions on them. I think we underestimate that, because of the delivery as well.

If my husband went, 'I've had a really rubbish day at work', he would have relayed the facts. I would have analysed that thought he'd spoken about it. I probably would have put my own emotions into the situation without realising he actually hadn't told me how he feels about it, other than it was rubbish.

I wonder if we need to do more with children when they are younger. If it's a girl and they've fallen over, we go, 'Oh that must have really hurt' but if it's a boy and they've fallen over I wonder how many parents go, 'Oh never mind, up you get, you're a big strong boy'. It's the gendered work that we do with children.

I think we're getting much better at that and I welcome it. I think we need to do a lot more to show men that actually, they are still men if they express their emotions and if they cry and get upset.

Dad Damon with Robin

The children's grief

Both of my children reacted very differently. The older one understood that little bit more whereas the younger one was like, 'Well, don't worry mummy, it will be ok, we'll go and put some coins in a well and wish for him to come back and he'll be back.'

That was tricky as well. You don't want to amp it up too much because you don't want them to be in distress, but I still wanted them to realise that that's not going to happen this time, it's really sad for all of us, but we're going to get through it together. It's been really, really tricky and both of them have gone through different stages.

Initially, there was that intense sadness and really missing him. Then after a while the reality set in that our life is very different now. We've had to move house, we have a different car, we go to a different school, everything is different, and we don't do the things that we did before. We're all that little bit sadder. That hopelessness sets in. It's enduring and for children, a year is like a lifetime.

Currently, my youngest deals with it by being ambivalent about the whole thing. He doesn't want to talk or think about it; it is what it is. My eldest is more, 'I don't want to talk about him because I hate him. I hate him for what he did and the decisions he made. If that's the way he was going to be then I'm better off without him'.

They have a right to feel angry because their whole world changed. Something that they loved and needed was taken from them, regardless of how it was taken.

If it was a car accident you'd feel angry, whatever it was. They don't have anything else to blame though, like a car or cancer or alcohol. The only thing they have to blame is him. Let him have his anger and hopefully, he'll work through that and move on to something else. If that helps him, then so be it.

Mia with her children

It can be really terrifying as a parent to watch all the phases they go through and really sad as well when you're not on the same page. For me, I've just gone with the flow. If they're feeling really low – and there have been suicidal feelings - we get them help and support for that. If they want to go to the burial ground, then we go. If they don't want to go – there were times where they haven't gone for a year – I don't push it. It's whatever they want to do.

Right now my eldest is like, 'Let's talk about all the bad stuff that he did'. And I'm like, 'Ok, let's talk about that'. It's still part of him and who he was. I don't feel the need to turn people who have died into gods, which is something I think that we do. I think we immortalise them.

Eventually, he'll come back around and feel a different way.

It's such an individual journey, and as a parent, you're going through your own journey as well, as a partner. There are days when I still feel absolutely terrible and they'll say 'Mum you seem sad, what's wrong?' I'll say 'I'm missing your dad a bit today,' and they say 'I can understand that'.

The other thing you think constantly is, 'What if something happens to me?' Where does that leave them?' You're one parent down. The fears that I and my children have, you don't have unless you've been bereaved.

READ: Mental Health Awareness: 10 shows that depict the reality of mental illness

Friends' reactions

Mostly, people vanished or it was compared to their divorces, or it was compared to their husbands working late. It was slightly different to that. I had one person say to me, 'You're really lucky, my husband is a d***. Another person made a joke and said, 'Oh my god, did you do it?'

People don't know what to say so they fill the gaps the best way they know how, and that is by inserting their own experiences. They think about their own marriages, but actually, that's not the thing to say when that's just happened.

With my children, people wouldn't touch them with a bargepole. It's presumed that it's a household with a lot of issues, with a lot of problems. It's like, 'Oh no, you don't want to be around that family'. They stopped being invited to birthday parties. Some parents stopped talking to me in the playground.

There were a couple of parents who made me food and gave me flowers. The class rep raised some money so we could get a zoo pass – so there were people that were phenomenal.

At the time, you notice more of the negative than you do of the positive. I noticed feeling really alone. No one understands, in a nutshell. I think people worry about wording, but you just go up to the person the same way you always did.

The other thing people do with suicide is they as a lot of questions. Was there life insurance? Had you had an argument the night before? All kinds of questions you would never normally ask somebody. It's this morbid fascination, but none of the support that you need.

Then there's the judgement. I had people saying to me, 'I really wouldn't have told them that's what he did'. I thought, 'Why not?' We have to have open discussions about suicide, and the fact is, their risk increases whether you talk about it or not. The only thing that can bring it down is by having those open discussions. If they had found out later, the trust would have been in ruins.

Mia and her children have been there for each other

Searching for a children's book

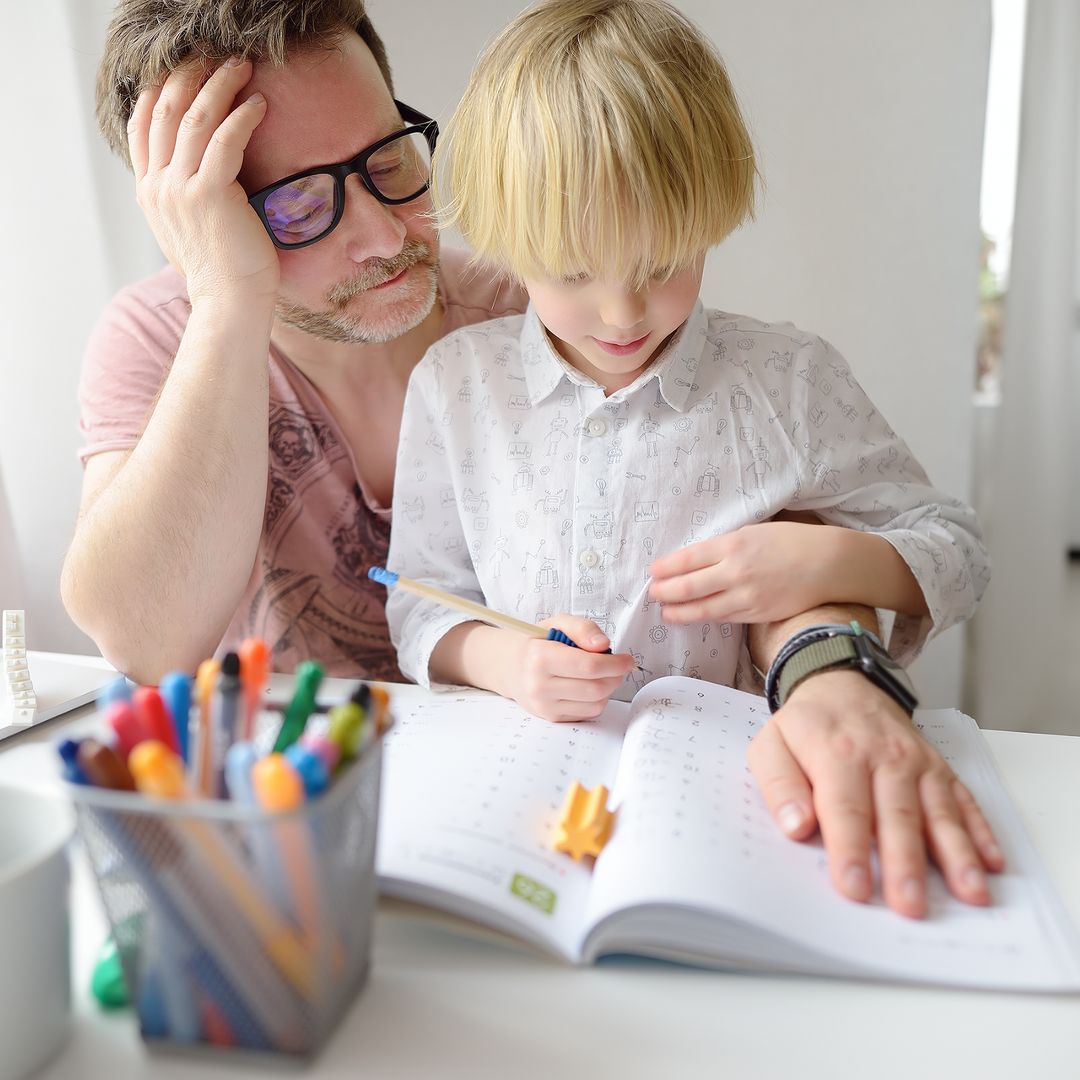

We phoned a number of charities at the time, but there weren't many books on the subject for children available. One I had cost a fortune to get from the US. It was really difficult to get hold of books around suicide, which comes with its own set of questions and issues. I read a lot of academic-based articles but none of that I could translate into, 'But what am I supposed to tell my kids?'

I was lucky that I was working in the Psychology department at the time where one Clinical Psychologist colleague said, 'Look, you've just got to be honest and clear with them,' and that was really, really helpful. Child Bereavement UK were absolutely phenomenal.

A lot of charities won't work with families straight after death – they want you to wait three or four months because they think it will be too overwhelming, that you're in shock so they won't be able to do any work with you. But actually, I don't think we needed anybody to do any work with us. We just needed somebody to listen that wouldn't be overwhelmed and traumatised themselves, who wouldn't give their opinion and who would understand what to say.

Writing the book together

It was quite organic. It started a long time ago. I remember the children being quite young and I think out of frustration I said something like, 'We should write our own book if we can't flippin' find one!'. I think it was my youngest who went, 'Yes, let's write a book'.

It didn't begin as a realistic idea. It was, 'Well what would you want people to know?' I jotted down a few notes for myself and then I kept asking as they went through the different stages. Then lockdown hit and I was just like, 'Let's do the book!'

My eldest started drawing some of the pictures. It was lovely, but to go right back into that from the beginning was quite a lot for both of them. So I'd check in with them every now and then with a question like, 'What do you think was important to do you when daddy first died?' then I'd jot it down. Then we asked on my Facebook if anyone wanted to contribute any drawings, and friends sent us some.

The cover of Mia, Robin and Jasper's book

Seeing the final book

I was really excited. I feel that even if one family reads this and finds it helpful, then for me, that's fantastic. Not only that, I felt really proud of the kids that they were able to verbalise their journeys and think about how it made them feel. The book is pretty much written in their words. It's something they will have forever as well.

I think they find it hard to picture another family out there right now who is hearing the news that they have heard. But hopefully, someone, somewhere, will have heard of the book and they can sit down and have a look at it and it might actually help parent or child process things just a little bit easier.

We wanted to make sure that the child's voice is being heard because as a mum, that's all you want to know. What is my child thinking right now? How can I be helpful and what helps them?

One in 29 schoolchildren are bereaved and suicide is said to be like bereavement with the volume turned up.

I wonder how many of those families are not saying that it's because of suicide, because there's still this opinion that you can't say it. They're alone in that fort and they've got nobody to talk to about how they're thinking and feeling because they daren't say it. I think that's so sad.

As a lecturer, it's now public knowledge and there will be students in my classroom that know. It's something very personal that's really out there now. I did wonder if it was a good idea, but then I remembered desperately to find something to read to my children, that would make sense to us as a family, and I thought, 'Forget it, just do it'.

My boys are so proud of the book. When they first saw it they said, 'It's an actual book'. I was like, 'Yes darling'.

The book Everything Changed can be purchased online HERE.

For emotional support you can call the Samaritans 24-hour helpline on 116 123, email jo@samaritans.org, visit a Samaritans branch in person or go to the Samaritans website.